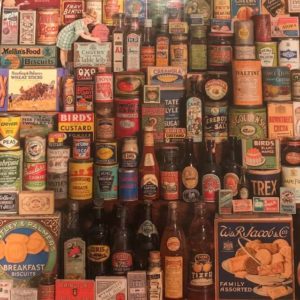

The Brands of Britain jigsaw bought in the Stationery House in Somerton is an essay in British social history. Some of the products, such as straw hat dye probably disappeared before the Second World War, others are still instantly recognizable from their presence on supermarket shelves today – Bird’s Custard and Marmite leapt out of the picture that forms the puzzle.

Looking at the picture, with its dozens and dozens of items that might have appeared in a weekly shopping basket, it would be easy to imagine that a larder in the 1960s was filled with colour and variety, that there would have been a multiplicity of labels offering distinctive taste and nutrition. Yet, familiar as the names might be, the presence of many of them among the weekly shop would have been infrequent. How often would a tin of Tate and Lyle’s Golden Syrup have been bought? The tin, with its image from the story of Samson in the Bible’s book of Judges, was a special treat. Scott’s Porage Oats, with a spoonful of Golden Syrup, was a treat on a winter morning. On all but the cold mornings, Kellogg’s Corn Flakes or Rice Krispies would have been a more familiar sight at breakfast time. Tins of biscuits, whether they were from Huntley and Palmer, or from Jacob’s, were encountered only at Christmas time, single packets were all that might appear in an ordinary shop.

Perhaps the Brands of Britain puzzle catches the eye not because of the commonplace nature of the labels it features, but because they represented the occasions when there was money to spare, the weeks when there were a few shillings available to buy those things that did not appear on the shopping list every week.

A typical week’s household expenditure would have probably not have included much that would have been thought worthy of inclusion in a picture for a jigsaw puzzle. Vegetables were plain and wholesome: potatoes, cabbage and cauliflower, carrots, swedes, turnips, and parsnips, peas and beans. The fruit bought regularly would have been apples, oranges and bananas. Meat meant mince, sausages, liver and kidneys, chops, and a joint for Sunday. There would not have been much variety, not much that would have been worthy of remark.

Yet, as repetitive as the diet might have been, its plainness, its freshness, its lack of preservatives and the assorted other additives now used, meant it was healthy. The Brands of Britain recalls a time before obesity and type two diabetes became common; perhaps the products should return to the shelves.

Is it possible to provide a link to a larger picture, for those of us with declining eyesight?

Apologies, I hadn’t clicked the link.