In June of this year, it was a privilege to visit the graves or memorials to High Ham men on the Western Front. Photographs were taken at each location, but some seem to have been lost.

Bryson Bellot Lieut. N.S.Y

In Memory of

Lieutenant BRYSON BELLOT

1st/1st, North Somerset Yeomanry

who died age 24

on 27 March 1918

Son of Hugh H. L. Bellot, D.C.L., and Beatrice V. Bellot,

of High Ham, Somerset.

Remembered with honour

INSCRIPTION

DEEPLY LOVED SON OF HUGH H. L. & BEATRICE V. BELLOT OF HIGH HAM

Buried at ABBEVILLE COMMUNAL CEMETERY EXTENSION

Location: Somme, France

Number of casualties: 2004

Cemetery/memorial reference: I. G. 28.

Bryson Bellot was born in Adddlestone, Surrey in 1894 to Beatrice Violette Bellot nee Clarke and Hugh Hale Leigh Bellot. His brother was Hugh Hale Bellot who was born 26th January 1890

Bryson Bellot standing in front of the windmill at High Ham

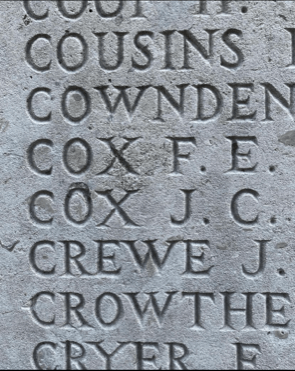

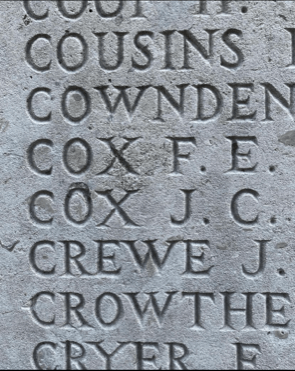

Francis E Cox Pte. Glouc. Regt.

Private COX, FRANCIS E.

Service Number 202139

Died 10/10/1917

Aged 21

1st/4th Bn.

Gloucestershire Regiment

Son of George and Eliza Sophia Cox, of Berefield Cottage, High Ham, Langport, Somerset.

Commemorated at TYNE COT MEMORIAL

Location: West-Vlaanderen, Belgium

Number of casualties: 34997

Cemetery/memorial reference: Panel 72 to 75.

Guy M Crossman 2nd Lt. Welch Regt.

Second Lieutenant

CROSSMAN, GUY DANVERS MAINWARING

Died 10/07/1916

Aged 31

13th Bn.

Welsh Regiment

Son of the Rev. Charles Danvers Crossman and Isabella Jane Crossman, of High Ham, Somerset. Joined Public Schools Service Battalion 1914.

WE THANK OUR GOD UPON EVERY REMEMBRANCE OF YOU

Buried at FLATIRON COPSE CEMETERY, MAMETZ

Location: Somme, France

Number of casualties: 1152

Cemetery/memorial reference: VI. D. 3.

Guy Danvers Mainwaring Crossman was born in High Ham in 1885 to Isabelle Jane and Charles Danvers Crossman. His brother was Norman Danvers Mainwaring Crossman who was born 1882. He lived at The Rectory, High Ham.

H C (Fred) Cullen Pte. S.L.I.

Private CULLEN, HENRY CHARLES

Service Number 26023

Died 17/02/1917

Aged 39

7th Bn.

Somerset Light Infantry

Husband of Elizabeth Ann Cullen, of High Ham, Langport, Somerset.

Buried at VARENNES MILITARY CEMETERY

Location: Somme, France

Number of casualties: 1219

Cemetery/memorial reference: I. I. 4.

C Victor Frith Pte. S.L.I.

Private FRITH, CHARLES VICTOR

Service Number 3796

Died 09/06/1917

Aged 28

1st Bn.

Honourable Artillery Company

Son of Samuel Stuckey Frith and Mary Frith, of Easton, Wells, Somerset.

Buried at DUISANS BRITISH CEMETERY, ETRUN

Location: Pas de Calais, France

Number of casualties: 3289

Cemetery/memorial reference: IV. J. 6.

Charles Victor Frith was born in Wells, Somerset, United Kingdom in 1888 to Mary and Samuel Stuckey Frith. His siblings were Emily M Frith born in 1869, Alfred George Frith born in 1870, Alice J Frith born in 1871, Edward R Frith born in 1874, Sarah Frith born in 1876, Harold Frith born in 1878, Athel Frith born in 1879, James Roy S Frith born in 1882, Eleana Frith born in 1885. They lived at the family home at Coxley Mill, Wells, Somerset.

In 1911 he lived at 19 Grosvenor Place, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire. In 1915 he lived at The Cottage, High Ham, Somerset

Percy T Garland Trpr. D.G.

Private

GARLAND, PERCY

Service Number 101479

Died 24/03/1918

3rd Dragoon Guards (Prince of Wales’ Own)

Commemorated at POZIERES MEMORIAL

Location: Somme, France

Number of casualties: 14708

Cemetery/memorial reference: Panel 1 and 2.

Percy Garland was born in High Ham in 1888.

Maurice Lloyd Gnr. R.G.A.

Gunner LLOYD, MAURICE

Service Number 129655

Died 13/05/1917

Aged 19

3rd Army Pool

Royal Garrison Artillery

Son of Joseph and Emma Jane Lloyd, of Fir Tree Farm, Low Ham, Langport, Somerset.

Buried at FEUCHY BRITISH CEMETERY

Location: Pas de Calais, France

Number of casualties: 211

Cemetery/memorial reference: II. B. 6.

Maurice Lloyd was born in Henley in 1898 to Joseph and Emma Jane Lloyd. His brothers were Joe V Lloyd born in 1896, Norman Lloyd born in 1901, and George Wallis Lloyd born in 1897. In 1911, he lived at Fir Tree Farm, Low Ham.

James R U Mead Corpl. W.S.Y.

Lance Corporal MEAD, JAMES ROBERT UTTERMARE

Service Number 27724

Died 05/08/1917

Aged 26

7th Bn.

Somerset Light Infantry

Son of Robert Uttermare Mead and Florence Martha Rose Mead, of “Inglenook,” Low Ham, Langport, Somerset. Six years service; also served at Gallipoli with the West Somerset Yeomanry.

Commemorated at YPRES (MENIN GATE) MEMORIAL

Location: West-Vlaanderen, Belgium

Number of casualties: 54612

Cemetery/memorial reference: Panel 21.

James Robert Uttermare Mead was born in Low Ham in 1891 to Florence Martha Rose and Robert Uttermare Mead.

T Champion D Mead Gnr. R.H.A.

Gunner MEAD, THOMAS CHAMPION DENHAM

Service Number 176964

Died 29/07/1917

Aged 24

“X” Bty. 17th Bde.

Royal Horse Artillery

Son of Robert Uttermare Mead and Florence Martha Rose Mead, of “Inglenook,” Low Ham, Langport, Somerset.

INSCRIPTION BELOVED SON OF ROBERT AND ROSE MEAD INGLENOOK, LOW HAM SOMERSET

Buried at MAROC BRITISH CEMETERY, GRENAY

Location: Pas de Calais, France

Number of casualties: 1124

Cemetery/memorial reference: II. H. 15.

Thomas Champion Denham Mead was born in Low Ham in 1894 to Florence Martha Rose and Robert Uttermare Mead.

Albert E J G Open L.Cpl. S.L.I.

Private OPEN, A E J G

Service Number 32270

Died 02/09/1918

12th (West Somerset Yeomanry) Bn.

Somerset Light Infantry

Buried at PERONNE COMMUNAL CEMETERY EXTENSION

Location: Somme, France

Number of casualties: 1424

Cemetery/memorial reference: III. D. 34.

Albert Edward Joseph George Open was born in Isle Brewers, Somerset in 1895.

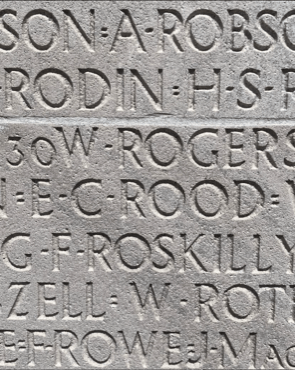

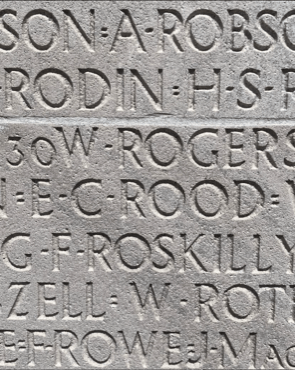

E Charles Rood Ptr. Can. Infy.

Private

ROOD, ERNEST CHARLES

Service Number 186322

Died 03/05/1917

Aged 24

27th Bn.

Canadian Infantry

Son of George and Elizabeth Ann Rood, of Henley, High Ham, Langport, Somerset, England.

Commemorated at VIMY MEMORIAL

Location: Pas de Calais, France

Number of casualties: 11242

Ernest Charles Rood was born in High Ham on 24th December 1892 to Elizabeth Ann and George Rood. His siblings were Albion Rood born in 1891, Hubert Rood born in 1897, Edith Rood born in 1900, and Lucy Ann Rood born in 1904. In 1911 they lived at Henley Corner, High Ham.

Walter H Townsend Pte. R.E.

Sapper TOWNSEND, WALTER

Service Number 166786

Died 19/10/1917

Aged 20

233rd Field Coy.

Royal Engineers

Youngest son of the late John and Clara Townsend, of King St., Swindon. Carpenter and Wheelwright.

Buried at Coxyde Military Cemetery

Walter Townsend was born in Swindon, Wiltshire in 1897.

Augustus Wilkins Pte. Can. Infy.

Private WILKINS, A

Service Number 255104

Died 02/09/1918

Aged 26

46th Bn.

Canadian Infantry

Son of William Dewdney Wilkins and Sarah Wilkins, of White House Farm, Henley, High Ham, Langport, Somerset, England.

Buried at DURY CRUCIFIX CEMETERY

Location: Pas de Calais, France

Number of casualties: 292

Cemetery/memorial reference: III. C. 22.

Augustus Wilkins was born in High Ham in 1894.