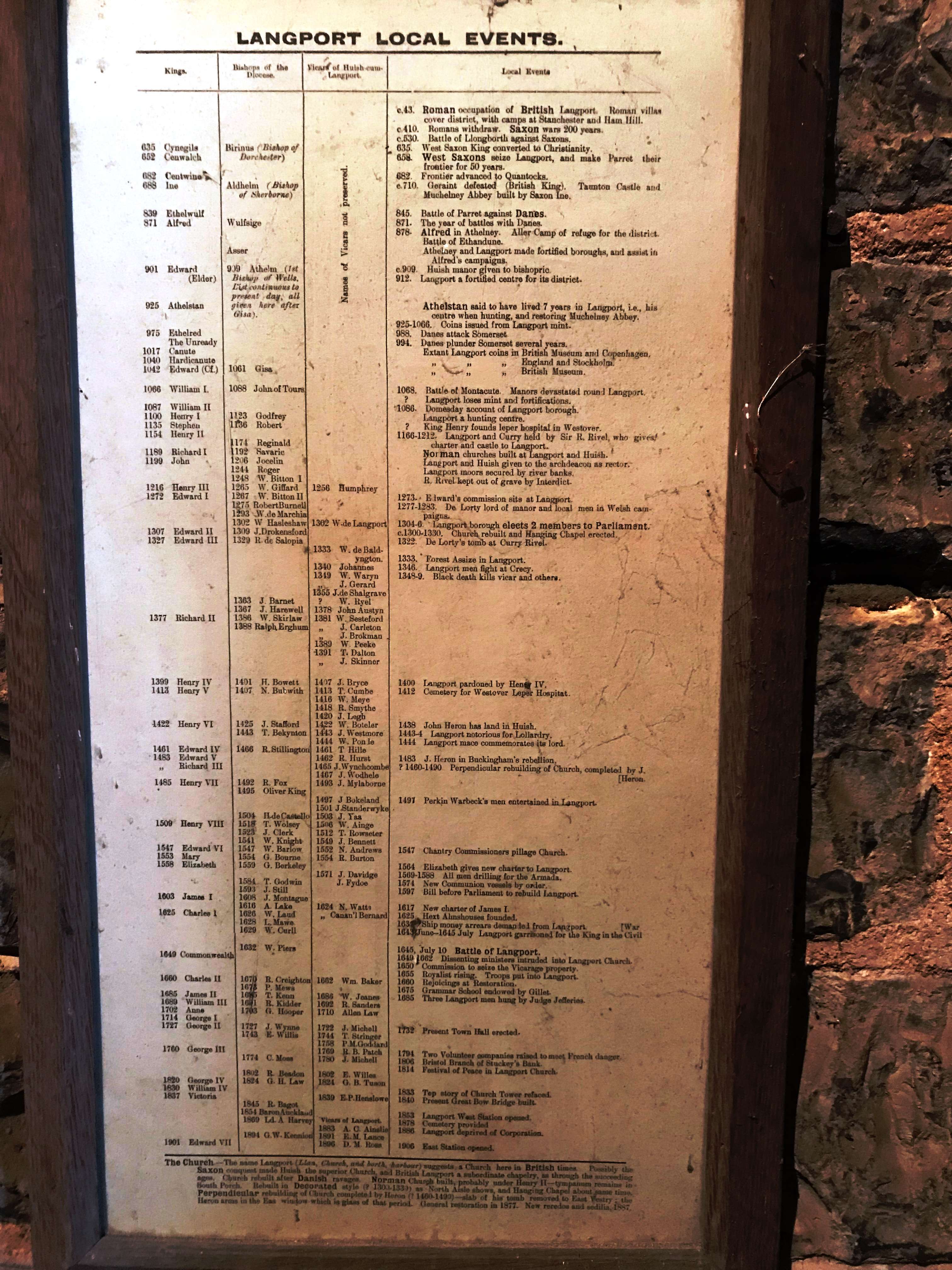

Declared redundant in 1994, Langport church is in the care of a conservation trust and is open to visitors. On the wall inside the west door there is a framed timeline from the Edwardian era. Titled “Langport Local Events”, it lists the bishops of the diocese and priests of the parish and provides a history of the town.

c. 43 Roman occupation of British Langport. Roman villas cover district, with camps at Stanchester and Ham Hill.

c. 410 Romans withdraw. Saxon wars 200 years

c.530 Battle of Llongborth against Saxons.

635 West Saxon King converted to Christianity.

654 West Saxons seize Langport, and make Parret their frontier for 50 years.

682 Frontier advanced to Quantocks.

c.710 Geraint defeated (British King). Taunton Castle and Muchelney Abbey built by Saxon Ine.

845 Battle of Parret against Danes.

871 The year of battles with Danes.

878 Alfred in Athelney. Aller Camp of refuge for the district.

Battle of Ethandune. Athelney and Langport made fortified boroughs, and assist in Alfred’s campaigns.

c.909 Huish manor Oven to bishopric

912 Langport a fortified centre for its district.

Athelstan said to have lived 7 years in Langport, i.e., his centre when hunting, and restoring Muchelney Abbey.

925-1066 Coins issued from Langport mint.

988 Danes attack Somerset

994 Danes plunder Somerset several years.

Extant Langport coins in British Museum and Copenhagen and Stockholm

1068 Battle of Montacute. Manors devastated round Langport.

Langport loses mint and fortifications.

1086 Domesday account of Langport borough. Langport a hunting centre.

King Henry founds leper hospital in Westover.

1166-1212 Langport and Curry held by Sir R. Rivel, who gives charter and castle to Langport. Norman man churches built at Langport and Huish. Langport and Huish given to the archdeacon as rector. Langport moors secured by river banks. R. Rivel kept out of grave by Interdict.

1273 Edward’s commission sits at Langport.

1277-1233 De Lorty lord of manor and local men in Welsh campaigns.

1304-6 Langport borough elects 2 members to Parliament.

c.1300-1330 Church rebuilt and Hanging Chapel erected.

1322 De Lorty’s tomb at Curry Rivel.

1333 Forest Assize in Langport.

1346 Langport men fight at Crecy.

1348-9 Black death kills vicar and others.

1400 Langport pardoned by Henry IV.

1412 Cemetery for Westover Leper Hospital.

1438 John Heron has land in Huish.

1443-4 Langport notorious for Lollardry.

1444 Langport mace commemorates its lord.

1483 J. Heron in Buckingham’s rebellion.

1460-1490 Perpendicular rebuilding of Church, completed by J. Heron.

1491 Perkin Warbeck’s men entertained in Langport.

1547 Chantry Commissioners pillage Church.

1564 Elizabeth gives new charter to Langport.

1569-1588 All men drilling for the Armada.

1571 New Communion vessels by order.

1597 Bill before Parliament to rebuild Langport.

1617 New charter of James I.

1625 Hext Almshouses founded.

1638 Ship money arrears demanded from Langport

1643 June-1645 July Langport garrisoned for the King in the Civil War

1645 July 10 Battle of Langport.

1662 Dissenting ministers intruded into Langport Church.

1650 Commission to seize the Vicarage property.

1655 Royalist rising. Troops put into Langport.

1660 Rejoicings at Restoration.

1675 Grammar School endowed by Gillet

1685 Three Langport men hang by Judge Jeffries

1732 Present Town Hall erected.

1794 Two Volunteer companies raised to meet French danger

1806 Bristol Branch of Stuckey’s Bank.

1814 Festival of Peace in Langport Church.

1840 Present Great Bow Bridge built.

1863 Langport West Station opened.

1878 Cemetery provided

1886 Langport deprived of Corporation.

1906 East Station opened.