A new sign appeared on the wall of the churchyard, “At this location there are Commonwealth War Graves, www.cwgc.org” There had often been stories in childhood years of those who had served during the First and Second World Wars, no-one had ever mentioned that there were casualties of the conflicts buried on familiar soil.

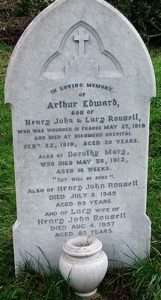

The graves include that of Private Arthur Roussell of the 1st Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment. He was twenty years old, his family name is now an unfamiliar one, his inscription reads:

In loving memory of Arthur Edward

son of Henry John and Lucy Russell,

who was wounded in France May 27 1918

and died at Richmond Hospital

Feby 22 1919, aged 20 years

Arthur Roussell’s father was a local police constable, the Roussell family home at South View, Huish Episcopi was in sight of the churchyard where the family had buried a ten week old daughter in 1910. It is hard to imagine their pain in losing their son from his injuries three months after the Armistice.

The History of the Lincolnshire Regiment describes how that day unfolded for the 1st Battalion, a day in the life of Arthur Roussell of Huish Episcopi:

At 8 p.m., a warning was received that an attack on a large scale was expected the following morning, to be preceded by a gas bombardment beginning at 1 a.m. All ranks were warned and gas guards posted.

This information was given by German prisoners captured by the XI French Corps on the left of the British. Besides this, our troops reported daily the arrival of reconnoitring parties of German officers, and the sound of guns being brought up every night.

The information was correct, for at 1 a.m. on the 27th of May a terrific bombardment by guns of every calibre opened on the front and back areas of the whole, Corps sector. Both high-explosive and gas shells were used in great quantities, the heaviest concentration being on the main line of resistance. The bombardment continued until about 4 a.m., when the enemy attacked under a thick smoke screen and mist as well.

Meanwhile the 1 st Lincolnshire, when the gas shelling began on the 27th, put on their gas masks and moved to assembly positions soon after 5 a.m. Just before 6 a.m. the enemy was reported to have gained a footing in the front line on the left of the brigade sector (held by the Northumberland Fusiliers). At 6.20 the battalion moved off — A and B Companies (Captain Samuelson and Lieutenant Carr) to the northern side of the Chalons-la- Vergeur— Cormicy road, covering La Chapelle, C and D Companies (Lieutenants Swaby and Tapsell) to the southern side of the road covering Cormicy, Battalion Headquarters on the same road in dug-outs near Brigade Headquarters.

Chalons-la-Vergeur was practically surrounded by wooded country, the village itself being near the south-western edge of a large forest which lay south-west of Cormicy. The road to the latter village lay through the woods. Only between Route 44 and Cormicy was the country clear of woods, but even that was a country of valleys and hills. The fighting, therefore, in which the Lincolnshire was to be involved, was to be difficult.

Very soon after the battalion had taken up positions a battalion was reported to have withdrawn from the front line, i.e., the left sub-sector of the brigade front. The Lincolnshire, therefore, formed a defensive flank on the left, the left of the battalion being in touch with some French Territorials who had been moved up to support. The defensive flank, under Captain Samuelson, was formed only just in time to prevent the enemy gaining a foothold in the wood. In the meantime, the enemy attacked north of Cormicy, but was repulsed with heavy losses. By 1 p.m. the situation became acute : the enemy had broken through and had completely worked round the left flank. On the right he had occupied Cormicy, where C and D Companies, after smashing three successive attacks, had been compelled to withdraw to another position. At 3 p.m., the battalion was ordered to fall back on the line of the Cormicy-Chalons-la-Vergeur road, as both flanks were in the air. A line was then formed facing north-west and continued along the line by the 4th Staffords. Here the enemy was held until 8 p.m. At that hour, however, Battalion Headquarters received a message that C and D Companies on the right were being hard pressed and that the Germans had worked completely round the left flank, occupying Chalons-la-Vergeur. The Lincolnshire were, therefore, almost surrounded and only a quick withdrawal could save them. Under cover of a rearguard which kept the enemy at bay, the battalion was extricated, and after getting clear of the Chalons-la-Vergeur road moved via Vaux Varennes to high ground near the Ferme de l’Epinette, north-east of Pevy. The time was now 1 a.m., 28th. Touch was obtained with the remainder of the brigade.

“The battalion was extricated,” among them a gravely wounded Private Arthur Roussell who would have been transferred to a casualty clearing station and then a military hospital before being taken back to the hospital at Richmond in Surrey. The pain endured by both he and his family between May 1918 and February 1919 is something at which, a century on, can only be guessed.

Remembrance must be about the names who are forgotten as well as those whom we remember.

You know the CWGC continue to use the cemetery on Hebron road in Kilkenny for those two graves I mentioned to you a while back. They are in the cemetery that was used by the mental hospital and the workhouse at the back of Nolan Pk.

I suppose back then there was very little movement within England, where the move was from countryside to countryside. With the exception of cases like this with the police, or as part of a household of some earl or duke with a few places.

It was the lack of movement and the geographical base of regiments, including the “pals” battalions, that meant heavy casualties sustained by a battalion could have a devastating effect upon a particular community. It is noticeable in the latter part of the war that men were assigned to battalions on a more dispersed basis. My great grandfather from Chiswick in the west of London, who enlisted at the age of 38, was in the Sussex regiment and was transferred to the Somerset Light Infantry, where he sustained gunshot wounds to his face, abdomen and thigh, and was then moved to the Labour Corps.